I know that I have said before that the Commonwealth is about done with its case-in-chief, but now I think it’s really true. Dave Chapman and Claude Worrell have called almost 40 witnesses. In Day 7 we heard from the two neuropathologists who gave detailed testimony about their detailed examination of Yeardley Love’s brain; we heard from the DNA expert to say which blood stains belonged to whom, and we heard from other forensic scientists, including a blood spatter expert, who finished putting all of the pieces together. I can’t think of anything else left to be testified to.

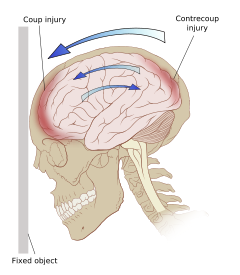

By far the most important point of the Day 7 evidence was the neuropathologists — one from MCV and one from UVA. Dr. Christine Fuller, from MCV, described three injuries to the brain that were not really apparent from the exterior, but were only apparent once the brain was dissected and examined microscopically. The first two injuries were on opposite sides of the brain — what is sometimes called a “coup-contrecoup” pattern. This pattern occurs when there is some sudden and very significant acceleration and deceleration of the head. The brain is a very fragile organ. It has been described as having the consistency of Jello. It is full of blood vessels and there is no internal structure to speak of. It is not really attached to the inside of the skull — it is sitting on top of the spinal cord, which is itself flexible.

To explain, let’s use an example given in a drawing on Wikipedia. Let’s say that my forehead strikes a wall with some force. The brain will be moving with the rest of the skull, but when the skull stops suddenly because it hits the wall, the brain keeps going (Newton’s first law), and strikes the inside of the skull in front — at the point of impact, or the “coup” injury. (“Coup” is French for “blow.”) The brain bounces off the inside front of the skull and then makes an impact against the inside of the skull in the rear, opposite the point of impact — the “contrecoup” injury. So neurologists know, when they see a coup-contrecoup pattern, that there has been a very sudden impact of the head against a hard and unyielding object. Dr. Fuller testified that this kind of injury can come from a fall, striking the head against a wall or the floor. It can come if the head is up against a wall and it is punched very hard; in this case, the skull is actually slightly bowed inward, causing an impact and injury; the brain is set in motion and strikes the other side of the skull, causing the second, or contrecoup, injury. The coup-contrecoup pattern can also come from a sudden acceleration/deceleration without an impact, like in a car accident — whiplash.

To explain, let’s use an example given in a drawing on Wikipedia. Let’s say that my forehead strikes a wall with some force. The brain will be moving with the rest of the skull, but when the skull stops suddenly because it hits the wall, the brain keeps going (Newton’s first law), and strikes the inside of the skull in front — at the point of impact, or the “coup” injury. (“Coup” is French for “blow.”) The brain bounces off the inside front of the skull and then makes an impact against the inside of the skull in the rear, opposite the point of impact — the “contrecoup” injury. So neurologists know, when they see a coup-contrecoup pattern, that there has been a very sudden impact of the head against a hard and unyielding object. Dr. Fuller testified that this kind of injury can come from a fall, striking the head against a wall or the floor. It can come if the head is up against a wall and it is punched very hard; in this case, the skull is actually slightly bowed inward, causing an impact and injury; the brain is set in motion and strikes the other side of the skull, causing the second, or contrecoup, injury. The coup-contrecoup pattern can also come from a sudden acceleration/deceleration without an impact, like in a car accident — whiplash.

Dr. Fuller also described another injury — bleeding at the brain stem, at the base of the skull. (Here I have to give a disclaimer — I could not be present during Day 7’s testimony, so all I know I get from notes from reporters. While the notes are pretty good, they are not as detailed as I would like here, and I am having to insert some knowledge gained from years of representing clients in personal injury cases as well. I’ll try to identify when I am adding my own knowledge, and when I am relying on what I know that the doctors actually said.) This kind of bleeding comes from the fact that there are a lot of blood vessels in the area around the brain stem, and when the acceleration/deceleration occurs, they can be torn. Other research shows that this kind of bleeding in the brain stem occurs in between 1 and 3% of brain injuries. When there is bleeding at the brain stem, this can damage the axons — the brain cells — in the area that control functions like breathing and heartbeat. Other research suggests that this kind of brain stem injury can be fatal in as many as 15-20% of cases. Dr. Fuller said that the kind of injury here could be immediately fatal, or death could come in a matter of hours. Dr. Fuller also testified that the injury to the brain stem can be seen from either acceleration and deceleration or from a twisting force.

A digression here, and I don’t know if it will matter…

From all press accounts of Dr. Fuller’s testimony, she testified that this injury could happen from either acceleration and deceleration of the head or from twisting. She apparently believed that a sudden twisting was responsible for this injury, but I do not understand her testimony to be that she was sure that there was twisting. As the Daily Progress reporter put it:

“It’s caused by blunt force trauma to the brain,” she said of the injuries. “The issue with how one gets contusions in the brain has to do with the brain moving separately from the skull.”

She explained that in a situation where the body is moving at some speed and then abruptly stopped, the brain may collide with the skull, causing damage. In cross-examination, Fuller said this sort of injury could “potentially” result from a fall.

A collision of the brain and skull involving some degree of torque, like what she said she thinks Love experienced, can cause other, more serious injuries, Fuller told jurors.

She explained that axons are extremely delicate neurotransmitters, and are even more fragile than blood vessels. Force, especially a twisting force, can cause these axons to rip, which in turn can cause small hemorrhages in the brain. On a photograph, Fuller identified several small hemorrhages that suggest Love may have suffered from an injury related to the rapid twisting of her head and neck.

Fuller said she considers hemorrhaging in “this distribution” to be the result of “blunt force trauma to the head.”

I highlighted the phrase “especially a twisting force” to make the point that Dr. Fuller’s testimony was not that these findings are explainable only by a twisting force. So when the Daily Progress’s headline reads, “Testimony centers on twisting of Love’s head,” that assumes as definite a possibility that the doctors do not believe to be definite. Because I anticipate that the defense will argue that the injuries were suffered in a fall, this could end up being important.

Dr. Marie-Beatriz Lopes then testified, and reinforced Dr. Fuller’s testimony. She noted one additional fact — Yeardley Love’s brain was heavier, more swollen, and redder than normal. I infer from that that she was saying that Yeardley Love’s brain was more blood-filled than the usual brain, though I am not sure what that tells us that is important to the case.

Dr. Fuller and Dr. Lopes testified that they believed that Yeardley Love lived for at least two hours after suffering the brain injury.

This gets to what is going to be a clear subtext to the argument about George Huguely’s criminal culpability — he “threw” (his word) her body on the bed and left, without calling for medical assistance. During the time that she lay there without medical assistance, she died. Trauma surgeons talk about the “golden hour” — that first hour after injury when permanent brain damage can be avoided or minimized, and lives saved, with prompt treatment. She died just blocks away from one of the finest neurological trauma units in the country. The Commonwealth will surely note that with a call to 911, Yeardley Love would still be with us.

Dr. William Gormley, the medical examiner, was recalled to the stand, and he gave his opinion that Yeardley Love died of cardiac arrhythmia, brought on by blunt force trauma to the head.

As I noted in my last post, there are many different causes for cardiac arrhythmia, and I expect that the defense experts — probably starting today — will try to make a major point of the fact that a significant number of deaths from cardiac arrhythmias occur without any identifiable reason. Or at least, without any reason identifiable upon the usual autopsy.

Throughout the cross-examination of all of the experts, it has been apparent that the defense is going to argue that the prolonged CPR efforts are responsible for many of the injuries that the doctors noted on and in Yeardley Love’s body. Dr. Gormley testified, for example, that there were indications of bruising of the heart that could have come from the chest compressions that are part of CPR. There has been much discussion of whether “reperfusion” — when blood is reintroduced into an area that had been without blood flow — could have caused some of the more minute findings. We will have to see how this theme is developed in the defense evidence.

The Commonwealth’s Attorney, Dave Chapman, has been very thorough. He has taken pains to anticipate, and to head off, potential defense arguments about alternative scientific explanations. In doing so, he gets to show that he, and his experts are thorough, basing their opinions not on press reports or initial impressions, but on an exhaustive review of all of the facts.

So what does this medical evidence mean for the different criminal charges?

If the defense gets into evidence the relative rarity of the axonal injury in the brain stem — 1 to 3% of cases — and the fact that such an injury is not invariably fatal (15-20%), the argument is set up that a fatal consequence of this kind of injury is not foreseeable. If death is not foreseeable, it begins to look much more like manslaughter than like murder.

Remember that involuntary manslaughter is defined in Virginia as involving an accident, contrary to the intention of the parties. If the jury believes that death was not foreseeable as a result of what George Huguely did — or, to be more precise, if the jury does not believe that the evidence establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that death was foreseeable as a result of what they believe that George Huguely did — then manslaughter begins to seem like the proper result.

And what of the failure to call 911? If the jury believes that George Huguely failed to call 911 knowing that she had been seriously injured, the jury could conclude that this showed a callousness or a hardness of heart that is evidence of malice. On the other hand, the jury could also interpret it as reflecting the fact that Huguely was drunk and not perceiving things as accurately as he might if he were sober. In that case, the jury might conclude that he was not being callous — just oblivious. Callousness is evidence of malice; obliviousness is not evidence of malice.

If this sounds like I am waffling, I am simply reflecting the truth that malice is what the jury says it is in a particular case. We can try to write precise definitions, and we will fail. We can try to talk about it in the abstract, and we will get unsatisfying results. Ultimately, malice is what the jury says it is.

As always, I recommend going to the WVIR website and go to “Day y” for a detailed description of the testimony.